Excerpt from the novel Snow Crash ![]()

![]() by Neal Stephenson

by Neal Stephenson ![]()

![]()

The Babel/Infocalypse card is resting in the middle of his desk. Hiro picks it up. The Librarian comes in.

Hiro is about to ask the Librarian whether he knows that Lagos is dead. But it’s a pointless question. The Librarian knows it, but he doesn’t. If he wanted to check the Library, he could find out in a few moments. But he wouldn’t really retain the information. He doesn’t have an independent memory. The Library is his memory, and he only uses small parts of it at once.

“What can you tell me about speaking in tongues?” Hiro says.

“The technical term is ‘glossolalia,'” the Librarian says.

“Technical term? Why bother to have a technical term for a religious ritual?”

The Librarian raises his eyebrows. “Oh, there’s a great deal of technical literature on the subject. It is a neurological phenomenon that is merely exploited in religious rituals.”

“It’s a Christian thing, right?”

“Pentecostal Christians think so, but they are deluding themselves. Pagan greeks did it—Plato called it theomania. The Oriental cults of the Roman Empire did it. Hudson Bay Eskimos, Chukchi shamans, Lapps, Yakuts, Semang pygmies, the North Borneo cults, the Trhi-speaking priests of Ghana. The Zulu Amandiki cult and the Chinese religious sect of Shang-ti-hui. Spirit mediums of Tonga and the Brazilian Umbanda cult. The Tungus tribesmen of Siberia say that when the shaman goes into his trance and raves incoherent syllables, he learns the entire language of Nature.”

“The language of Nature.”

“Yes, sir. The Sukuma people of Africa say that the language is kinaturu, the tongue of the ancestors of all magicians, who are thought to have descended from one particular tribe.”

“What causes it?”

“If mystical explanations are ruled out, then it seems that glossolalia comes from structures buried deep within the brain, common to all people.”

“What does it look like? How do these people act?”

“C.W. Shumway observed the Los Angeles revival of 1906 and noted six basic symptoms: complete loss of rational control; dominance of emotion that leads to hysteria; absence of thought or will; automatic functioning of the speech organs; amnesia; and occasional sporadic physical manifestations such as jerking or twitching. Eusebius observed similar phenomena around the year 300, saying that the false prophet begins by a deliberate suppression of conscious thought, and ends in a delirium over which he has no control.”

“What’s the Christian justification for this? Is there anything in the Bible that backs this up?”

“Pentecost.”

“You mentioned that word earlier—what is it?”

“From the Greek pentekostos, meaning fiftieth. It refers to the fiftieth day after the Crucifixion.”

“Juanita just told me that Christianity was hijacked by viral influences when it was only fifty days old. She must have been talking about this. What is it?”

“‘And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance. Now there were dwelling in Jerusalem Jews, devout men from every nation under heaven. And at this sound the multitude came together, and they were bewildered, because each one heard them speaking in his own language. And they were amazed and wondered, saying, “Are not all these who are speaking Galileans? And how is it that we hear, each of us in his own native language? Parthians and Medes and Elamites and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabians, we hear them telling in our own tongues the mighty works of God.” And all were amazed and perplexed, saying to one another, “What does this mean?”‘ Acts 2:4-12.”

“Damned if I know,” Hiro says. “Sounds like Babel in reverse.”

“Yes, sir. Many Pentecostal Christians believe that the gift of tongues was given to them so that they could spread their religion to other peoples without having to actually learn their language. The word for that is ‘xenoglossy.'”

“That’s what Rife was claiming in that piece of videotape, on top of the Enterprise. He said he could understand what those Bangledeshis were saying.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Does that really work?”

“In the sixteenth century, Saint Louis Bertrand allegedly used the gift of tongues to convert somewhere between thirty thousand and three hundred thousand South American Indians to Christianity,” the Librarian says.

“Wow. Spread through that population even faster than smallpox.”

What did the Jews think of this Pentecost thing?” Hiro says. “They were stil running the country, right?”

“The Romans were running the country,” the Librarian says, “but there were a number of Jewish religious authorities. At this time, there were three groups of Jews: the Pharisees, the Sadducees, and the Essenes.”

“I remember the Pharisees from Jesus Christ, Superstar. They were the ones with deep voices who were always hassling Christ.”

“They were hassling him,” the Librarian says, “because they were religiously very strict. They adhered to a strong legalistic version of the religion; to them, the Law was everything. Clearly, Jesus was a threat to them because he was proposing, in effect, to do away with the Law.”

“He wanted a contract renegotiation with God.”

“This sounds like an analogy, which I am not very good at—but even if it is taken literally, it is true.”

“Who were the other two groups?”

“The Sadducees were materialists.”

“Meaning what? They drove BMWs?”

“No. Materialists in the phisosophical sense. All philosophies are either monist or dualist. Monists believe that the material world is the only world—hence, materialists. Dualists believe in a binary universe, that there is a spiritual world in addition to the material world.”

“Well, as a computer geek, I have to believe in the binary universe.”

The Librarian raises his eyebrows. “How does that follow?”

“Sorry. It’s a joke. A bad pun. See, computers use binary code to represent information. So I was joking that I have to believe in the binary universe, that I have to be a dualist.”

“How droll,” the Librarian says, not sounding very amused. “Your joke may not be without genuine merit, however.”

“How’s that? I was just kidding, really.”

“Computers rely on the one and the zero to represent all things. This distinction between something and nothing—this pivotal separation between being and nonbeing—is quite fundamental and underlies many Creation myths.”

Hiro feels his face getting slightly warm, feels himself getting annoyed. He suspects that the Librarian may be pulling his leg, playing him for a fool. But he knows that the Librarian, however convincingly rendered he may be, is just a piece of software and cannot actually do such things.

“Even the word ‘science’ comes from an Indo-European root meaning ‘to cut’ or ‘to separate.’ The same root led to the word ‘shit,’ which of course means to separate living flesh from nonliving waste. The same root gave us ‘scythe’ and ‘scissors’ and ‘schism,’ which have obvious connections to the concept of separation.”

“How about ‘sword’?”

“From a root with several meanings. One of those meanings is ‘to cut or pierce.’ One of them is ‘post’ or ‘rod.’ And the other is, simply, ‘to speak.'”

“Let’s stay on track,” Hiro says.

“Fine. I can return to this potential conversation fork at a later time, if you desire.”

“I don’t want to get all forked up at this point. Tell me about the third group—the Essenes.”

“They lived communally and believed that physical and spiritual cleanliness were intimately connected. They were constantly bathing themselves, lying naked under the sun, purging themselves with enemas, and going to extreme lengths to make sure that their food was pure and uncontaminated. They even had their own version of the Gospels in which Jesus healed possessed people, not with miracles, but by driving parasites, such as tapeworm, out of their body. These parasites are considered to be synonymous with demons.”

“They sound kind of like hippies.”

“The connection has been made before, but it is faulty in many ways. The Essenes were strictly religious and would never have taken drugs.”

“So to them there was no difference between infection with a parasite, like tapeworm, and demonic possession.”

“Correct.”

“Interesting. I wonder what they would have thought about computer viruses?”

“Speculation is not in my ambit.”

“Speaking of which—Lagos was babbling to me about viruses and infection and something called a nam-shub. What does that mean?”

“Nam-shub is a word from Sumerian.”

“Sumerian?”

“Yes, sir. Used in Mesopotamia until roughly 2000 B.C. The oldest of all written languages.”

“Oh. So all other languages are descended from it?”

For a moment, the Librarian’s eyes glance upward, as if he’s thinking about something. This is a visual cue to inform Hiro that he’s making a momentary raid on the Library.

“Actually, no,” the Librarian says. “No languages whatsoever are descended from Sumerian. It is an agglutinative tongue, meaning that it is a collection of morphemes or syllables that are grouped into words—very unusual.”

“You are saying,” Hiro says, remembering Da5id in the hospital, “that if I could hear someone speaking Sumerian, it would sound like a long stream of short syllables strung together.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Would it sound anything like glossolalia?”

“Judgment call. Ask someone real,” the Librarian says.

“Does it sound like any modern tongue?”

“There is no provable genetic relationship between Sumerian and any tongue that came afterward.”

“That’s odd. My Mesopotamian history is rusty,” Hiro says. “What happened to the Sumerians? Genocide?”

“No, sir. They were conquered, but there’s no evidence of genocide per se.”

“Everyone gets conquered sooner or later,” Hiro says. “But their languages don’t die out. Why did Sumerian disappear?”

“Since I am just a piece of code, I would be on very thin ice to speculate,” the Librarian says.

“Okay. Does anyone understand Sumerian?”

“Yes, at any given time, it appears that there are roughly ten people in the world who can read it.”

“Where do they work?”

“One in Israel. One at the British Museum. One in Iraq. One at the University of Chicago. One at the University of Pennsylvania. And five at Rife Bible College in Houston, Texas.”

“Nice distribution. And have any of these people figured out what the word ‘nam-shub’ means in Sumerian?”

“Yes. A nam-shub is a speech with magical force. The closest English equivalent would be ‘incantation,’ but this has a number of incorrect connotations.”

“Did the Sumerians believe in magic?”

The Librarian shakes his head minutely. “This is the kind of seemingly precise question that is in fact very profound, that pieces of software, such as myself, are notoriously clumsy at. Allow me to quote from Kramer, Samuel Noah, and Maier, John R. Myths of Enki, the Crafty God. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989: ‘Religion, magic, and medicine are so completely intertwined in Mesopotamia that separating them is frustrating and perhaps futile work…. [Sumerian incantations] demonstrate an intimate connection between the religious, the magical, and the esthetic so complete that any attempt to pull one away from the other will distort the whole.’ There is more material in here that might help explain the subject.”

“In where?”

“In the next room,” the Librarian says, gesturing at the wall. He walks over and slides the rice-paper partitionout of the way.

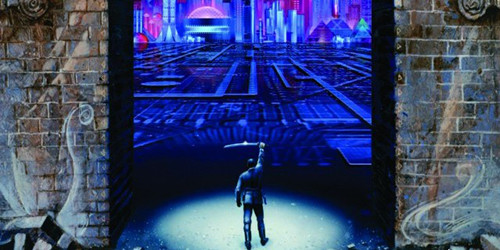

A speech with magical force. Nowadays, people don’t believe in these kinds of things. Except in the Metaverse, that is, where magic is possible. The Metaverse is a fictional structure made out of code. And code is just a form of speech—the form that computers understand. The Metaverse in its entirety could be considered a single vast nam-shub, enacting itself on L. Bob Rife’s fiber-optic network.

The voice phone rings. “Just a second,” Hiro says.

“Take your time,” the Librarian says, not adding the obvious reminder that he can wait for a million years if need be.

“Me again,” Y.T. says. “I’m still on the train. Stumps got off at Express Port 127.”

“Hmmm. That’s the antipode of Downtown. I mean, it’s as far away from Downtown as you can get.”

“It is?”

“Yeah. One-two-seven is two to the seventh power minus one—”

“Spare me, I take your word for it. It’s definitely out in the middle of fucking nowhere,” she says.

“You didn’t get off and follow him?”

“Are you kidding? All the way out there? It’s ten thousand miles from the nearest building, Hiro.”

She has a point. The Metaverse was built with plenty of room to expand. Almost all of the development is within two or three Express Ports—five hundred kilometers or so—of Downtown. Port 127 is twenty thousand miles away.

“What is there?”

“A black cube exactly twenty miles on a side.”

“Totally black?”

“Yeah.”

“How can you measure a black cube that big?”

“I’m riding along looking at the stars, okay? Suddenly, I can’t see them anymore on the right side of the train. I start counting local ports. I count sixteen of them. We get to Express Port 127, and Stumpy climbs off and goes toward the black thing. I count sixteen more local ports and then the stars come out. Then I take thirty-two kilometers and multiply it by point six and I get twenty miles—you asshole.”

“That’s good,” Hiro says. “That’s good intel.”

“Who do you think owns a black cube twenty miles across?”

“Just going on pure, irrational bias, I’m guessing L. Bob Rife. Supposedly, he has a big hunk of real estate out in the middle of nowhere where he keeps all the guts of the Metaverse. Some of us used to smash into it occasionally when we were out racing motorcycles.”

“Well, gotta go, pod.”