Excerpt from the novel Snow Crash

by Neal Stephenson

by Neal Stephenson

Y.T. doesn’t get down to Long Beach very much, but when she does, she will do just about anything to avoid the Sacrifice Zone. It’s an abandoned shipyard the size of a small town. It sticks out into San Pedro Bay, where the older, nastier Burbclaves of the Basin—unplanned Burbclaves of tiny asbestos-shingled houses patrolled by beetle-browned Kampuchean men with pump shotguns—fade off into the foam-kissed beaches. Most of it’s on the appropriately named Terminal Island, and since her plank doesn’t run on the water, that means she can only get in or out by one access road.

Like all Sacrifice Zones, this one has a fence around it, with yellow metal signs wired to it every few yards.

SACRIFICE ZONE

WARNING. The National Parks Service has declared this area to be a National Sacrifice Zone. The Sacrifice Zone Program was developed to manage parcels of land whose clean-up cost exceeds their total future economic value.

And like all Sacrifice Zone fences, this one has holes in it and is partially torn down in places. Young men blasted out of their minds on natural and artificial male hormones must have some place to do their idiotic coming-of-age rituals. They come in from Burbclaves all over the area in their four-wheel-drive trucks and tear across the open ground, slicing long curling gashes into the clay cap that was placed on the really bad parts to prevent windblown asbestos from blizzarding down over Disneyland.

Y.T. is oddly satisfied to know that these boys have never even dreamed of an all-terrain vehicle like Ng’s motorized wheelchair. It veers off the paved road with no loss in speed—ride gets a little bumpy—and hits the chain-link fence as if it were a fog bank, plowing a hundred-foot section into the ground.

It is a clear night, and so the Sacrifice Zone glitters, an immense carpet of broken glass and shredded asbestos. A hundred feet away, some seagulls are tearing at the belly of a dead German shepherd lying on its back. There is a constant undulation of the ground that makes the shattered glass flash and twinkle; this is caused by vast sparse migrations of rats. The deep, computer-designed imprints of suburban boys’ fat knobby tires paint giant runes on the clay, like the mystery figures in Peru that Y.T.’s mom learned about at the NeoAquarian Temple. Through the windows, Y.T. can hear occasional bursts of either firecrackers or gunfire.

She can also hear Ng making new, even stranger sounds with his mouth.

There is a built-in speaker system in this van—a stereo, though far be it from Ng to actually listen to any tunes. Y.T. can feel it turning on, can sense a nearly inaudible hiss coming from the speakers.

The van begins to creep forward across the Zone.

The inaudible hiss gathers itself up into a low electronic hum. It’s not steady, it wavers up and down, staying pretty low, like Roadkill fooling around with his electric bass. Ng keeps changing the direction of the van, as though he’s searching for something, and Y.T. gets the sense that the pitch of the hum is rising.

It’s definitely rising, building up in the direction of a squeal. Ng snarls a command and the volume is reduced. He’s driving very slowly now.

”It is possible that you might not have to buy and Snow Crash at all,” he mumbles. “We may have found an unprotected stash.”

”What is this totally irritating noise?”

”Biolelectric sensor. Human cell membranes. Grown in vitro, which means in glass—in a test tube. One side is exposed to outside air, the other side is clean. When a foreign substance penetrates the cell membrane to the clean side, it’s detected. The more foreign molecules penetrate, the higher the pitch of the sound.”

”Like a Geiger counter?”

”Very much like a Geiger counter for cell-penetrating compounds,” Ng says.

Like what? Y.T. wants to ask. But she doesn’t.

Ng stops the van. He turns on some lights—very dim lights. That’s how anal this guy is—he has gone to the trouble to install special dim lights in addition to all the bright ones.

They are looking into a sort of bowl, right at the foot of a major drum heap, that is strewn with litter. Most of the litter is empty beer cans. In the middle is a fire pit. Many tire tracks converge here.

”Ah, this is good,” Ng says. “A place where the young men gather to take drugs.”

Y.T. rolls her eyes at this display a tubularity. This must be the guy who writes all those antidrug pamphlets they get at school.

Like he’s not getting a million gallons of drugs every second through all of those gross tubes.

”I don’t see any signs of booby traps,” Ng says. “Why don’t you go out and see what kind of drug paraphernalia is out there.”

She looks at him like, what did you say?

”There’s a toxics mask hanging on the back of your seat,” he says.

”What’s out there, toxic-wise?”

”Discarded asbestos from the shipbuilding industry. Marine antifouling paints that are full of heavy metals. They used PCBs for a lot of things, too.”

”Great.”

”I sense your reluctance. But if we can get a sample of Snow Crash from this drug-taking site, it will obviate the rest of our mission.”

”Well, since you put it that way,” Y.T. says, and grabs the mask. It’s a big rubber-and-canvas number that covers he whole head and neck. Feels heavy and awkward at first, but whoever designed it had the right idea, all the weight rests in the right places. There’s also a pair of heavy gloves that she hauls on. They are way too big. Like the people at the glove factory never dreamed that an actual female could wear gloves.

She trudges out onto the glass-and-asbestos soil of the Zone, hoping that Ng isn’t going to slam the door shut and drive away and leave her there.

Actually, she wishes he would. It would be a cool adventure.

Anyway, she goes up to the middle of the “drug-taking site.” Is not too surprised to see a little nest of discarded hypodermic needles. And some tiny little empty vials. She picks up a couple of the vials, reads their labels.

”What did you find?” Ng says when she gets back into the van, peels off the mask.

”Needles. Mostly Hyponarxes. But there’s also a couple of Ultra Laminars and some Mosquito twenty-fives.”

”What does all this mean?”

”Hyponarx you can get at any Buy ‘n’ Fly, people call them rusty nails, they are cheap and dull. Supposedly the needles of poor black diabetics and junkies. Ultra Laminars and Mosquitoes are hip, you get them around fancy Burbclaves, they don’t hurt as much when you stick them in, and they have better design. You know, ergonomic plungers, hip color schemes.”

”What drug were they injecting?”

”Checkitout,” Y.T. says, and holds up one of the vials toward Ng.

Then it occurs to her that he can’t exactly turn his head to look.

”Where do I hold it so you can see it?” she says.

Ng sings a little song. A robot arm unfolds itself from the ceiling of the van, crisply yanks the vial from her hand, swings it around, and holds it in front of a video camera set into the dashboard.

The typewritten label stuck onto the vial says, just “Testosterone.”

”Ha ha, a false alarm,” Ng says. The van suddenly rips forward, starts heading right into the middle of the Sacrifice Zone.

”Want to tell me what’s going on?” Y.T. says, “since I have to actually do the work in this outfit?”

”Cell walls,” Ng says. “The detector finds any chemical that penetrates cell walls. So we homed in naturally on a source of testosterone. A red herring. How amusing. You see, our biochemists lead sheltered lives, did not anticipate that some people would be so mentally warped as to use hormones like there were some kind of drug. How bizarre.”

Y.T. smiles to herself. She really likes the idea of living in a world where someone like Ng can get off calling someone else bizarre. “What are you looking for?”

”Snow Crash,” Ng says. “Instead, we found the Ring of Seventeen.”

”Snow Crash is the drug that comes in the little tubes,” Y.T. says. “I know that. What’s the Ring of Seventeen? One of those crazy new rock groups that kids listen to nowadays?”

”Snow Crash penetrates the walls of brain cells and goes to the nucleus where the DNA is stored. So for purposes of this mission, we developed a detector that would enable us to find cell wall-penetrating compounds in the air. But we didn’t count on heaps of empty testosterone vials being scattered all over the place. All steroids—artificial hormones—share the same basic structure, a ring of seventeen atoms that acts like a magic key that allows them to pass through cell walls. That’s why steroids are such powerful substances when they are unleashed in the human body. They can go deep inside the cell, into the nucleus, and actually change the way the cell functions.

”To summarize: the detector is useless. A stealthy approach will not work. So we go back to the original plan. You buy some Snow Crash and throw it up in the air.”

Y.T. doesn’t quite understand that last part yet. But she shuts up for a while, because in her opinion, Ng needs to pay more attention to his driving.

Once they get out of that really creepy part, most of the Sacrifice Zone turns out to consist of a wilderness of dry brown weeds and large abandoned hunks of metal. There are big heaps of shit rising up from place to place—coal or slag or coke or smelt or something.

Every time they come around a corner, they encounter a little plantation of vegetables, tended by Asians or South Americans. Y.T. gets the impression that Ng wants to just run them over, but he always changes his mind at the last instant and swerves around them.

Some Spanish-speaking blacks are playing baseball on a broad flat area, using the round lids of fifty-five-gallon drums as bases. They have parked half a dozen old beaters around the edges of the field and turned on their headlights to provide illumination. Nearby is a bar built into a crappy mobile home, marked with a graffiti sign: THE SACRIFICE ZONE. Lines of boxcars are stranded in a yard of rusted-over railway spurs, nopal growing between the ties. One of the boxcars has been turned into a Reverend Wayne’s Pearly Gates franchise, and evangelical CentroAmericans are lined up to do their penance and speak in tongues below the neon Elvis. There are no NeoAquarian Temple franchises in the Sacrifice Zone.

”The warehouse area is not as dirty as the first place we went,” Ng says reassuringly, “so the fact that you can’t use the toxics mask won’t be so bad. You may smell some Chill fumes.”

Y.T. does a double take at this new phenomenon: Ng using the street name for a controlled substance. “You mean Freon?” she says.

”Yes. The man who is the object of our inquiry is horizontally diversified. That is, he deals in a number of different substances. But he got his start in Freon. He is the biggest Chill wholesaler/retailer on the West Coast.”

Finally, Y.T. gets it. Ng’s van is air-conditioned. Not with one of those shitty ozone-safe air conditioners, but with the real thing, a heavy metal, high-capacity, bone-chilling Frigidaire bilzzard blaster. It must use and incredible amount of Freon.

For all practical purposes, that air conditioner is a part of Ng’s body. Y.T.’s driving around with the world’s only Freon junkie.

”You buy your supply of Chill from this guy?”

”Until now, yes. But for the future, I have an arrangement with someone else.”

Someone else. The Mafia.

Like this:

Like Loading...

![]()

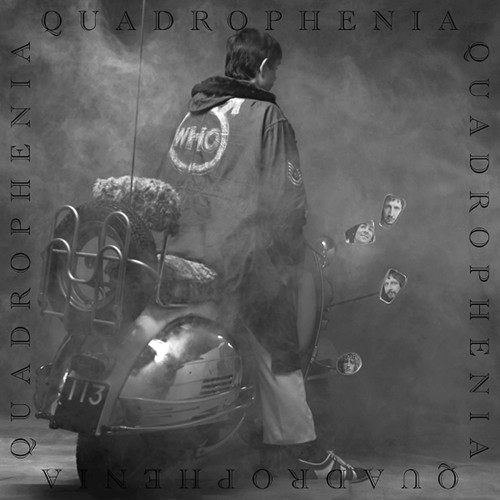

![]() (track 15 from the Quadrophenia LP by The Who

(track 15 from the Quadrophenia LP by The Who ![]()

![]() )

)